No false moves

The Australian sovereign and semi-government bond market faced game-changing challenges in 2020. Greatly increased issuance requirements seem baked in for the foreseeable future, but those most responsible for distributing and trading the bonds appear relatively confident that – despite resumed volatility in late February – the market is set up well for the pandemic end game.

Laurence Davison Head of Content and Editor KANGANEWS

Australia had a white-piece advantage when it came to mitigating the impact of COVID-19. Remote island status and relatively swift government action – that was broadly accepted by the population – helped mitigate the pandemic’s most devastating public-health impact.

Almost exactly a year after the first cases of COVID-19 reached its shores, Australia has experienced fewer than 30,000 total infections and fewer than 1,000 fatalities from the virus. On a per-capita basis, these figures are respectively 75 times and more than 40 times lower than the impact in the US.

At the same time, key sectors – most notably commodities, where extraction and export continued almost uninterrupted – helped shield Australia from the worst of the economic fallout. The domestic economy began reopening as early as mid-2020 and, with the notable exception of a virus outbreak in Victoria later in the year, has by February 2020 only experienced temporary setbacks on the long path back to normality.

Key indicators are rebounding. Some, including the housing market, are doing so fast. Others have defied expectation. Unemployment was hovering at around 5 per cent going into the pandemic and hit 7.5 per cent by mid-year 2020 but fell to 6.6 per cent by the end of the year – confounding expectations of a rate of 10 per cent or more from the early days of lockdown.

By late February 2020, expectations of a faster-than-expected recovery saw Australia leading global sovereign-bond markets in a dramatic sell off. This dynamic seems to rest on a view that rate rises are not as far away as central-bank rhetoric insists they are.

Domestic bond traders are unconvinced that such a dramatic reversal is the most likely outcome. For one thing, recovery still has a long way to run. Australia’s national pandemic lockdown, while brief from an international perspective, hammered hospitality, tourism, education and much of the retail sector. The reopening has been cautious and is not yet complete, so many businesses in the worst-affected sectors remain on life support.

It was clear from relatively early in Australia’s crisis that public-sector balance sheets were going to carry a lot of the burden. Politicians and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) referred repeatedly to support packages as “the bridge” to take a largely mothballed economy to reopening, hopefully without too much structural damage. As well as the reserve bank’s own stimulus, the bridge’s structural supports would be founded on the funding tasks of the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) and the state treasury corporations.

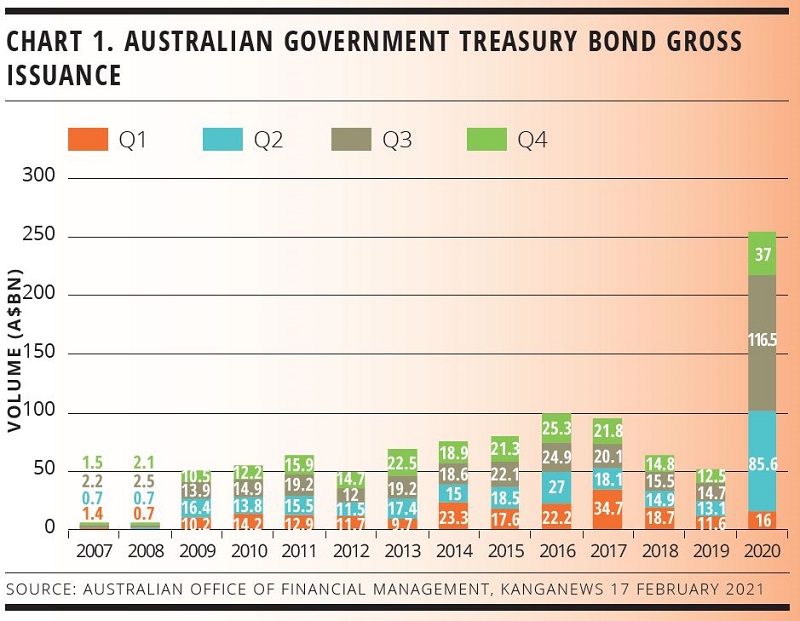

AOFM issuance in 2020, especially in the middle of the year, illustrates the scale of the task (see chart 1). Before the financial crisis in 2008-9, there was a live debate about whether the Australian sovereign should retire all its debt or keep a nominal supply on issue to maintain a pricing curve. New Australian Treasury bond issuance subsequently rose to a shade more than A$50 billion (US$38.3 billion) in 2009 and reached its post-financial-crisis, pre-pandemic peak of just less than A$100 billion in 2016. The 2020 figure was A$255 billion, of which the AOFM issued A$202 billion in the second and third quarters.

It is a similar story at state level, albeit with some variation between states. The second lockdown following a COVID-19 outbreak centred on Melbourne helped push Treasury Corporation of Victoria (TCV)’s 2020/21 funding requirement up to A$45.8 billion – a more than fivefold increase on the preceding year.

New South Wales Treasury Corporation (TCorp) expects to issue around A$25 billion more in 2020/21 than its last pre-pandemic year – though it was projecting a big increase even prior to COVID-19 – and Queensland Treasury Corporation (QTC) expects to add A$10 billion-plus to its own supply.

It will be hard for the RBA to manage targeting inflation at a somewhat elevated level while allowing current yield to be more reflective of the same outcome, all without causing systemic problems in other asset classes. Ongoing QE could be the tool used to manage the glide path to higher rates.

OPENING GAMBIT

Numbers like the eventual borrowing requirements were not known in the early days of the crisis. But it was eminently clear that there would be a lot more funding to do, and in many respects the early weeks of the pandemic period played out like the opening of a grandmasters’ chess game: undeniably complex but following a well-established path of move and countermove.

In March-April 2020, Australian government-sector issuers had little opportunity to get ahead of their newly bloated issuance tasks. “The first thing global investors did at the start of the crisis was de-risk and repatriate funds,” says Michael Hendrie, managing director and head of fixed income client coverage at UBS in Sydney. “Global fund managers’ focus at the time was on selling what they could – and Australian bonds are liquid. With credit spreads widening by 50 basis points or more it was a fairly straightforward choice to divest.”

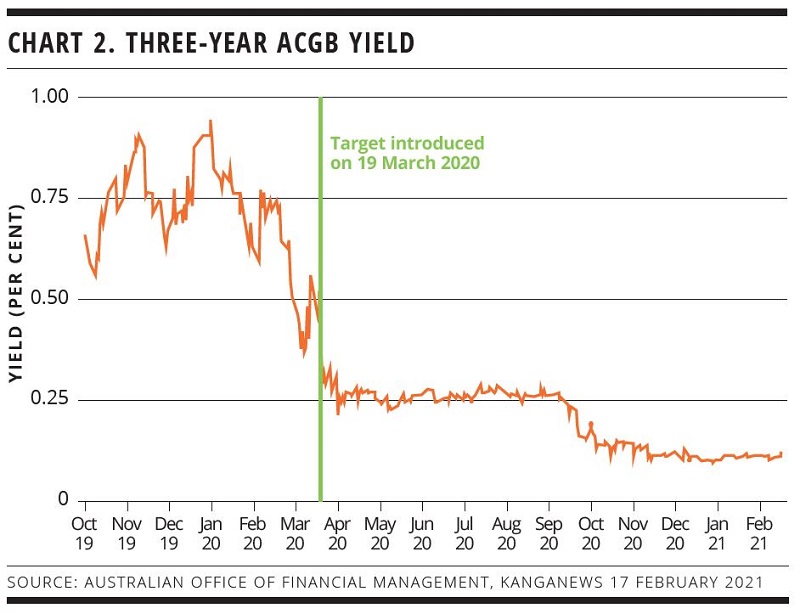

Central-bank response was effectively mandated and proceeded more or less as expected. On 19 March, the RBA announced it would purchase Australian Commonwealth government bonds (ACGBs) and semi-government debt in quantities sufficient to keep the three-year sovereign yield at around 0.25 per cent and to “address market dislocations”.

This was a hard-and-early strategy designed to settle the market with the promise of all the force the RBA could bring to bear. The central bank initiated yield-curve control (YCC) with no cap on the volume of bonds it was prepared to buy, and by the end of April it had absorbed more than A$50 billion in the secondary market.

The impact was immediate and long-lasting. Three-year ACGB yield hit the RBA’s target within a few days and held there until market expectations shifted to an even lower YCC target – which the RBA duly delivered, at 0.1 per cent, at its November monetary policy meeting (see chart 2).

The volume of RBA bond purchases was clearly significant, but a primary immediate consequence of YCC was to arrest the slide in market functionality. “At the start of RBA intervention the whole construct was a pure confidence play,” says Ian Ravenscroft, Sydney-based director, government bond trading at ANZ. “Confidence was completely shot at the time and the market needed affirmation that there would be an alternative way to distribute the large uptick in supply.”

VARIATION

The process of restoring market confidence and function was undeniably concerning for issuers and traders alike – but it was also a relatively short one. Having purchased more than A$50 billion of bonds between 20 March and the end of April, the RBA felt the need to acquire just A$21.5 billion for YCC purposes from May last year to the end of January 2021.

Meanwhile, semi-government borrowers were able to return to short-term markets relatively quickly, were active in term private placements during March and resumed syndicated benchmark issuance in short order. TCorp priced a syndicated three- and four-year transaction for total volume of A$3.2 billion on 2 April, and within a week Australian Capital Territory, QTC, South Australian Government Financing Authority and TCV added a further A$3.5 billion of new term issuance.

A key investor base – at this stage and throughout 2020 – was the asset-liability management books of Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs). The local banking sector experienced an influx of liquidity relatively early in the crisis as corporates accumulated defensive cash positions, households preserved their own cash balances and the government’s superannuation early-release scheme saw thousands of Australians withdraw pension funds to cover potential loss of income.

At the same time as it introduced YCC, the RBA also debuted its term funding facility (TFF) to provide Australian banks direct three-year funding at a fixed rate of 0.25 per cent. ADIs did not draw on the TFF in large size immediately, but the shift in deposit patterns – which was also driven by the reduced discretionary spending options available to locked-down households – meant they were suffuse with liquidity anyway. Their later use of the TFF only added to the pool.

Andrew Bryan, director, government bond trading at Deutsche Bank in Sydney, says: “Without the RBA and the ADIs, the volume of ACGBs and semi-government bonds issued last year would have been a very hard sell. The RBA has bought more than A$130 billion so far and the ADIs have bought more than A$100 billion in the same period. Fundamentally, this is where the bonds have gone.”

The return of market functionality did not mean the RBA’s intervention was done. In November, at the same time as it lowered the YCC target and the official cash rate to 0.1 per cent, the reserve bank introduced its first programme of official QE. This was a further A$100 billion of ACGB and semi-government purchases, this time with the goal of supporting the economic recovery and in particular job creation.

The RBA used its February 2021 monetary-policy announcement to disclose plans for a second QE package, also of A$100 billion, even though it was barely half-way through distributing the first one at the time.

CONFIDENCE AND QUANTITY

The RBA’s intervention programme is at a curious juncture early in 2021. Initially largely designed to support market functionality, by deploying QE1 and QE2 the RBA has made clear that it is now in the full-fledged fiscal stimulus game. Meanwhile, the emergence of a conducive new-issuance market after the first few weeks of 2021 and a temporary halt in YCC purchases suggest the market-confidence goal may be less relevant.

Traders say, however, that the RBA backstop should not be underestimated even when the market is benign. Adam Donaldson, Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s Sydney-based head of macro sales, tells KangaNews: “Knowing there is a buyer for A$5 billion every single week remains a very important support for the market. This is significant volume – it can actually mean negative net new issuance in some weeks – and the pressure that may have been on the market is certainly alleviated by it.”

This also hints at the evolving nature of the RBA’s challenge – one that is also faced by those that need to interpret the central bank’s plans and respond to its actions. The RBA’s balance sheet has grown from coastal raider to dreadnaught status. Westpac Banking Corporation’s chief economist, Bill Evans, estimated the RBA’s balance sheet would reach around 27.5 per cent of national GDP even before the announcement of QE2 – rapidly closing in on the US Federal Reserve’s equivalent figure of 34 per cent.

The impact is being felt in some quarters of the bond market, albeit only at the margin so far. Donaldson continues: “Part of the RBA’s mandate when it first intervened in early 2020 was to assist market functioning. But there is a balancing act between market function and the proportion of individual ACGB and semi-government bond lines the RBA owns.”

Donaldson suggests the RBA has bought a sufficient proportion of certain lines – for instance semi-government green bonds – that the free float of paper is quite limited and they trade unusually expensive. The ACGB curve is not immune to this effect: so much of the April 2024 bond, the current target point for YCC, is now in RBA hands that on occasion it has traded special and been hard to source to cover short positions.

James Davey, director, Australian dollar semi-government and SSA trading at Deutsche Bank in Sydney, comments: “RBA activity has not yet caused dysfunction in the market, in the sense that there are no semi lines on which we would not bid given there is always the QE backstop. But there is a much keener eye on relative value now and every basis point is important – a 2 basis point widening of TCorp over QTC, for instance, is sufficient to bring in substantial demand for switching.”

Some market users believe the RBA could go some way to managing the ripple effects of its intervention by taking a more dynamic approach to its QE purchases, in effect applying the market-function goal of YCC to the wider programme while maintaining the volume target for QE overall. This idea is not universally supported, however (see box).

Flex on, flex off: optionality in RBA investment

The Reserve Bank of Australia could contemplate varying the pace of its QE bond purchases as a counterbalance to market sentiment, some dealers argue. Others say this level of dynamism would be outside the reserve bank’s comfort zone and may be unhelpful anyway.

At present, the RBA has committed to deploying its aggregate A$200 billion (US$153 billion) of QE at a fixed pace of A$5 billion each week. This is a different strategy from the yield-curve control (YCC) programme, which has no fixed volume for overall purchases or their velocity. Instead, YCC allocations are made when the RBA feels they are needed to keep sovereign-bond yield around the target level or to support market function.

Adam Donaldson, head of macro sales at Commonwealth Bank of Australia, thinks a YCC-type approach could be used to at least some extent in the QE programme. “We think the RBA should maintain a market-function perspective, recognising that this is an important part of its role alongside the stimulus objective,” he suggests.

RBA funds, Donaldson argues, should be available to support the market in circumstances like a significant widening of spreads that make it hard for the states to fund themselves.

NEW PLAYERS

Indeed, dealers say the RBA’s involvement has helped the market reach a relatively healthy point. Investors have not been crowded out by the central bank, and the second half of 2020 and the first months of the new year have featured many positive signals for international participation.

“As last year wore on, spreads tightened and RBA policy evolved, we saw the market diversify,” Donaldson says. “Moving into 2021, there is general awareness of a good amount of offshore, real-money and hedge-fund interest in the sector. This wasn’t the case earlier in the crisis.”

Some of these accounts are involved precisely because of the RBA’s presence, specifically because of a trading strategy based on an Australian equivalent of the “Fed put”. Hendrie reveals that a number of global investors have set up strategies to take advantage of opportunities between the AOFM’s increased issuance, and the RBA’s YCC and QE.

He adds: “I wouldn’t call this an arbitrage because it isn’t a one-way bet. The RBA.clearly has a significant influence over our bond market, but given we’re part of a global market it doesn’t control pricing on its own. But it is certainly an opportunity, and one that.has aroused global interest particularly from hedge funds.”

This point was largely proved in late February as a global bond sell-off saw long-end ACGB yield spike and even the three-year point pop above the YCC target.

A range of factors is attracting investors to Australian dollar bonds. For instance, Davey says S&P Global Ratings downgrades that pushed TCorp and TCV into the double-A band in December last year actually appear to have promoted a broadening of global investor interest in the semi-government sector.

Now none of the Australian semi-government issuers are universally triple-A rated, global investors that were previously constrained by a top rating requirement have generally elected to abandon this mandate restriction rather than exit the sector entirely. This means they can buy more of the semi-government issuer names.

Meanwhile, dramatically reduced Australian dollar issuance from supranational, sovereign and agency (SSA) issuers has compelled many of these entities’ biggest buyers to look at Australian semi-governments.

Davey says this has not prompted large-scale buying but it has supported price tension and relative-value opportunities for all investors. “It is providing liquidity for domestic real money to sell SSAs and move back into semis at times when offshore investors view Australian dollar SSAs as good value relative to what they are being shown in US dollars and euros.”

THE LONG GAME

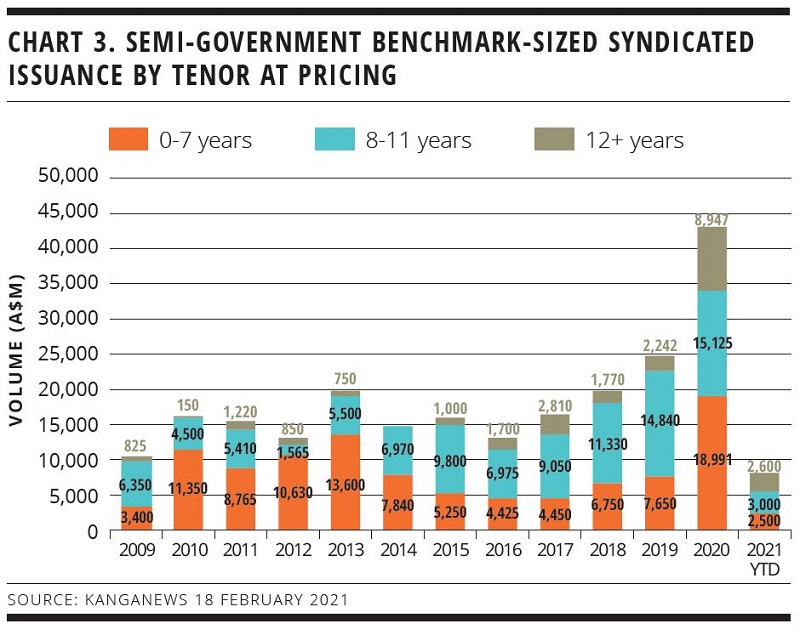

A widening investor base has opened up issuance opportunities that borrowers facing much larger funding tasks have gratefully accepted. Syndicated semi-government issuance leapt to an unprecedented A$43.1 billion in 2020, or nearly twice the total of any previous year. But it was the A$8.9 billion of ultra-long – tenor of 12 years or more – issuance that really caught the eye, coming in at more than three times the previous record (see chart 3). The A$2.6 billion of such issuance in 2021 to mid-February has already surpassed the full-year figure from all but two years.

Dealers point to developments like a “material number” of large Japanese investors increasing their portfolio allocations to Australian dollars during 2020 as a driver of the long-dated opportunity. This has brought a degree of volatility risk, as re-emerged in the late February sell-off.

It has never been suggested that the Australian market is immune to volatility events. These could pose a challenge to issuers with larger tasks and thus less capacity to pause issuance while storms clear. However, market users are confident that Australian government-sector borrowers are sufficiently progressed with what should be their peak new-issuance requirements to manage around volatility events (see box).

Issuance on hold: managing around volatility

Despite record funding tasks, a productive period for new issuance in H2 2020 and into the new year means Australian sovereign and semi-government issuers should have breathing room sufficient to obviate the need to issue into less supportive market conditions.

It cannot be denied that, all else being equal, larger funding tasks mean issuers have less ability to step back from markets for extended periods. Chris Barrington, head of fixed income investor sales at ANZ, tells KangaNews: “I’m sure the most frequent issuers view themselves as price takers and aim to be active through the cycle. As we have seen with the AOFM [Australian Office of Financial Management] and semis over the last 12 months, maintaining a flexible approach to funding pays dividends, especially in volatile markets. Issuers want to execute their larger transactions during positive market periods and maintaining flexibility is key.”

In general, dealers credit Australian sovereign and semi-government borrowers with a successful response to changing issuance requirements and market conditions – that is the product of robust engagement and flexible primary-market strategies.

Overall, the presence of more and larger investors is clearly another supportive factor for the Australian high-grade market. “Demand has evolved in a way that has been very positive for issuers – for instance allowing them to issue more at the long end, which they are very keen to do,” Ravenscroft confirms. “This has also perhaps freed up a bit of liquidity in mid-curve bonds that otherwise would be quite tightly held by domestic ADIs. The dynamic of investor demand growth has been very conducive of issuance evolution for the semis in particular.”

This evolution is also starting to have a positive impact on long-end trading liquidity. The Australian dollar rates market has historically offered good liquidity out to the 10-year futures basket then become progressively patchier further out on the curve.

There are some positive signs, though to date still at the margin. Hendrie says semi-government liquidity is now solid out to 2032 maturity bonds and and he is confident issuers should find demand sufficient to double the size of even the larger lines at this duration, to around A$3-4 billion apiece.

Donaldson adds: “We have found the semis to be very responsive to investor demand, which can help trading books accommodate demand without having to hold large inventory. This is an encouraging development.”

RBA ENDGAME

The next big question for the Australian bond complex is a challenging one, but also the product of an improving economic picture: when and how the RBA will start the process of dialling back unconventional policy. The universal market expectation is that QE will be the last of the three primary measures – the others being the TFF and YCC – that the RBA seeks to unwind.

Opinion is divided on the likely longevity of YCC. Hendrie says: “The RBA has said it will only remove YCC when it is confident it can achieve employment and inflation targets that it hasn’t hit for the past 10 years. This is a relatively high hurdle but three years is a long time, so the market will likely challenge this policy as the vaccine is rolled out and stronger data continues.”

Others suspect a move on YCC may come sooner. Ravenscroft says the base case for ANZ’s analysts is that the RBA will not roll YCC onto the November 2024 maturity ACGB from the current target bond, the April 2024.

ANZ’s Sydney-based head of fixed income investor sales, Chris Barrington, notes that withdrawal of any stimulus measure does not have to be permanent. Even the possibility of a programme being reinstated may be sufficient to obviate the need to do so. “Once stability and liquidity return, the market is likely to assume that even when a stimulus tool is wound back or withdrawn it can always be brought back into play,” Barrington explains.

On the other hand, ongoing QE in Australia is baked into most market users’ expectations. This includes a likely third or even fourth package, though the size and focus of future injections could vary.

Bryan, for instance, says the nature and purpose of QE has evolved to become a tool the RBA may effectively be compelled to use. The reserve bank is confronting conflicting factors: a need to push inflation back toward the target band, even as its bond purchases are suppressing term premium.

“It will be hard for the RBA to manage targeting inflation at a somewhat elevated level – toward the top end of the band – while allowing current yield to be more reflective of the same outcome, all without causing systemic problems in other asset classes,” Bryan tells KangaNews. “Ongoing QE could be the tool used to manage the glide path to higher rates.”

Meanwhile, the RBA will also be keenly aware that it does not exist in a vacuum. The Australian dollar has already appreciated considerably and withdrawal of QE while other countries still have the taps on full blast will inevitably see the currency rise and erode the economic gains stimulus has supported.

Ravenscroft suggests: “The RBA will certainly be cognisant of not tapering too early when its international peers are maintaining stimulus for an extended period. If the Australian economy continues to improve as expected this is going to be the central conversation in our market throughout the year.”

WOMEN IN CAPITAL MARKETS Yearbook 2021

KangaNews's annual yearbook amplifying female voices in the Australian capital market.

HIGH-GRADE ISSUERS YEARBOOK 2021

The ultimate guide to Australian and New Zealand government-sector borrowers.

KANGANEWS SUSTAINABLE FINANCE H2 2021

KangaNews is proud to share cutting-edge information from the global and Australasian sustainable debt market.