The real economy: down with APP?

The real-economy consequences of infinite QE may prove inescapably problematic for the euro area. The erosion of savings and pensions, and concurrent asset-price inflation, have undoubtedly contributed to the political upheaval that is being felt across the continent.

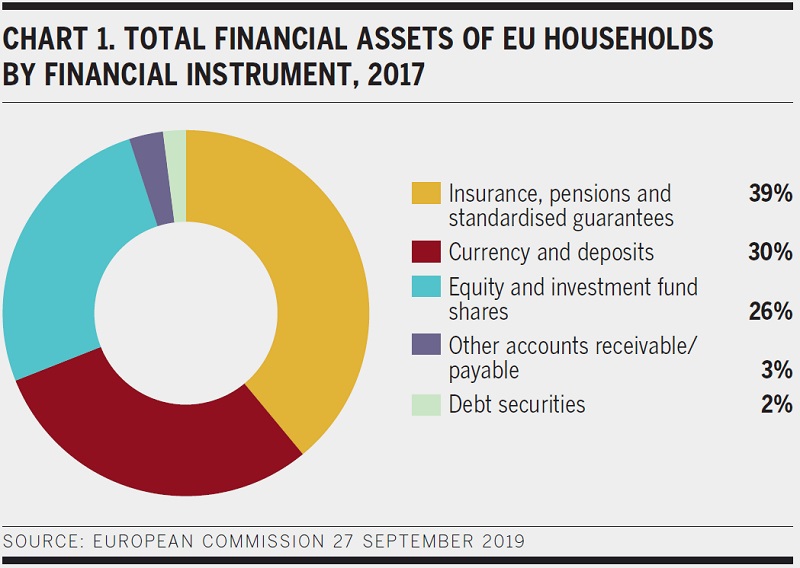

EU households tend to have a relatively low allocation of financial assets to instruments, such as equity, which are likely to benefit from a low-rate-driven surge in asset prices.

In fact, as of 2017 nearly 70 per cent of EU household financial assets were in securities which are likely to have their value further eroded by negative interest rates (see chart 1).

Meanwhile, the Bank for International Settlements released its annual economic report in June 2019 with the warning that monetary policy cannot be the engine for economic growth.

It says: “As the global financial crisis broke out, central banks prevented it from spiralling out of control and then successfully supported the recovery. At the same time… following serious financially induced downturns and given stubbornly subdued inflation, there are diminishing returns and costs in relying too much on monetary policy.”

While the European Central Bank (ECB)’s policies may enable cheaper funding for borrowers it is unclear whether the transmission mechanism for benefits to the wider European economy will prevail.

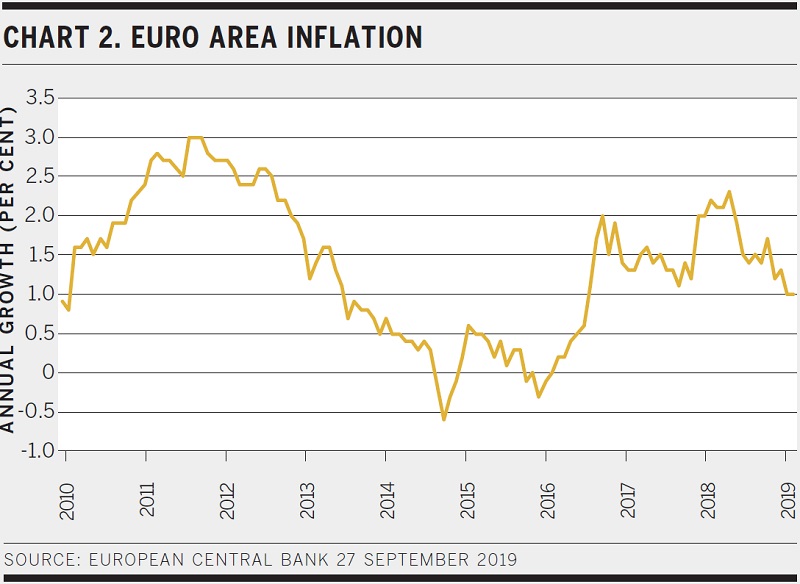

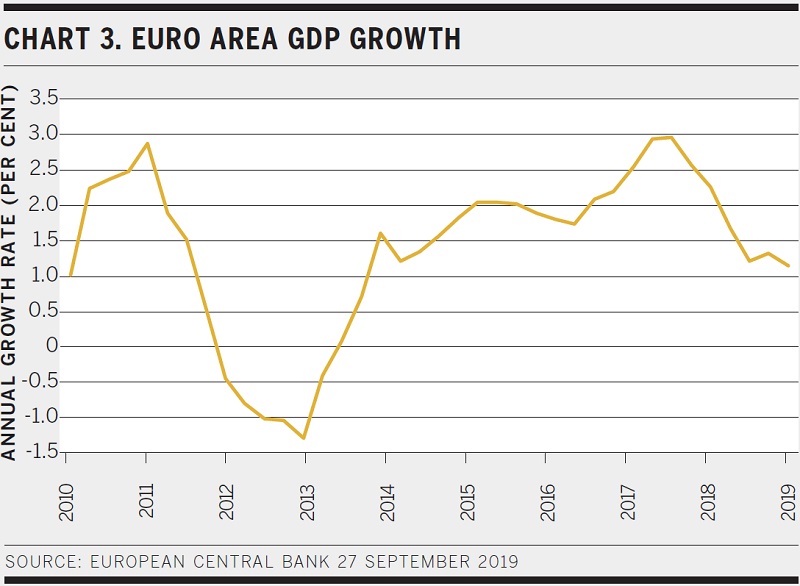

There was a significant uptick in inflation and GDP growth following the ECB’s initial QE deployment (see charts 2 and 3). Both stagnated during 2017 and 2018, however, and then began to reverse almost immediately after QE temporarily ended.

Downward revisions to projected inflation and inflation expectations led to the latest ECB policy decision. As a TD Securities (TD) research note from 12 September states: “The rate outlook is tied to the outlook for inflation, with the ECB’s inflation forecasts becoming more important than ever.”

However, negative interest rates and QE have not demonstrated a sustained stimulation of inflation so far and it is debateable whether lowering the euro area’s deposit rate further into negative territory will produce a different result. The move could serve further to squeeze banks’ ability to operate.

Impact on financials

Negative rates impede banks’ ability to make profit, even with the tiering system introduced by the ECB. A BNP Paribas research note published on 18 September estimates that European banks could be better off by just €4 billion (US$4.4 billion) per year thanks to ECB deposit tiering.

In a speech on 25 June, ECB vice president, Luis de Guindos, said while euro area banks’ profitability has recovered from the trough following the European sovereign-debt crisis, return on equity, at around 6 per cent, was still short of a cost of capital estimated at 8-10 per cent for most banks.

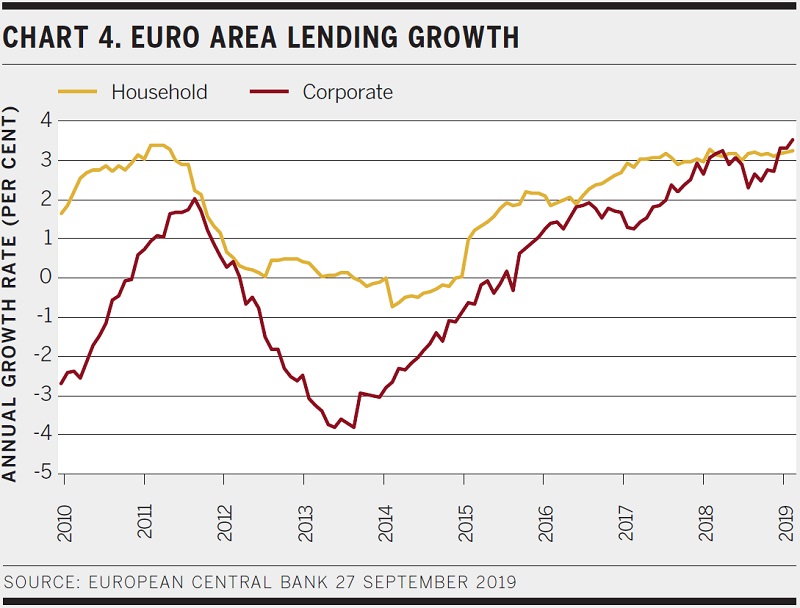

Inability to generate profit hampers banks’ capability of generating capital organically, de Guindos added, and “makes it harder for them to build up buffers against unexpected shocks and limits their capacity to fund loan growth”. This is presumably where the ECB hopes cheaper cost of wholesale funds will spur lending activity, as it did in 2015 when QE was first introduced in the euro area (see chart 4).

Lending in the euro area clearly picked up in 2015, particularly in the household sector. But it stagnated through 2017 and 2018 even though the asset-purchase programme continued. Whether a fresh injection of QE can provide another boost remains to be seen.

Bernd Volk, head of covered bond and agency research at Deutsche Bank, says the way the ECB interprets its inflation mandate has an inherent conflict. “Core inflation has been stable for many years but is consistently below the target rate of 2 per cent. If the ECB instead defined its mandate as achieving no risk of deflation and no risk of uncontrolled inflation it would be setting monetary policy closer to neutral and avoiding the conflict with a higher reversal rate and financial stability.”

There is a sense that the ECB’s stimulus measures, though not unsubstantial, may be pushing on a piece of string. The overall effect on the European real economy could be modest at best.

TD’s analysts estimate the ECB will deliver a further 10 basis points of deposit rate cuts in December and again in March 2020, and that QE will be increased to €40 billion per month as the global macro environment worsens.

The ECB could be painted into a corner. It struggled to build up ammunition while the European economy was growing and governments are hesitant to release the valves of fiscal policy. There appear to be few options the ECB can take other than to keep painting.